Hashimoto’s Disease: Symptoms, Causes & Treatment

Hashimoto's Disease

What is Hashimoto’s Disease?

Hashimoto’s disease is named after Japanese surgeon Hakaru Hashimoto, who first diagnosed the condition in 1912. It’s an autoimmune condition in which the immune system turns against the thyroid gland, thus leading to hypothyroidism or underactive thyroid.

Also known as autoimmune thyroiditis, chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis or Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, Hashimoto’s disease is the most widespread thyroid condition in America, affecting around 14 million people. It’s seven times more common in women than in men and most commonly occurs between age 45 and 65.

The thyroid gland is a little gland at the front part of your neck. It produces T3 and T4 hormones that control how your body consumes energy. In Hashimoto’s disease, very low amounts of thyroid hormones are produced, which can result in problems all over the body, such as brain function and heart rate, as well as metabolism. As a result, problems with the body’s conversion of food to energy are common. A goiter can develop, which is a non-cancerous swelling at the front of your neck.

Hashimoto’s disease is less common in children, but in areas where there’s insufficient iodine in diets, a sizable proportion of children can contract the disease.

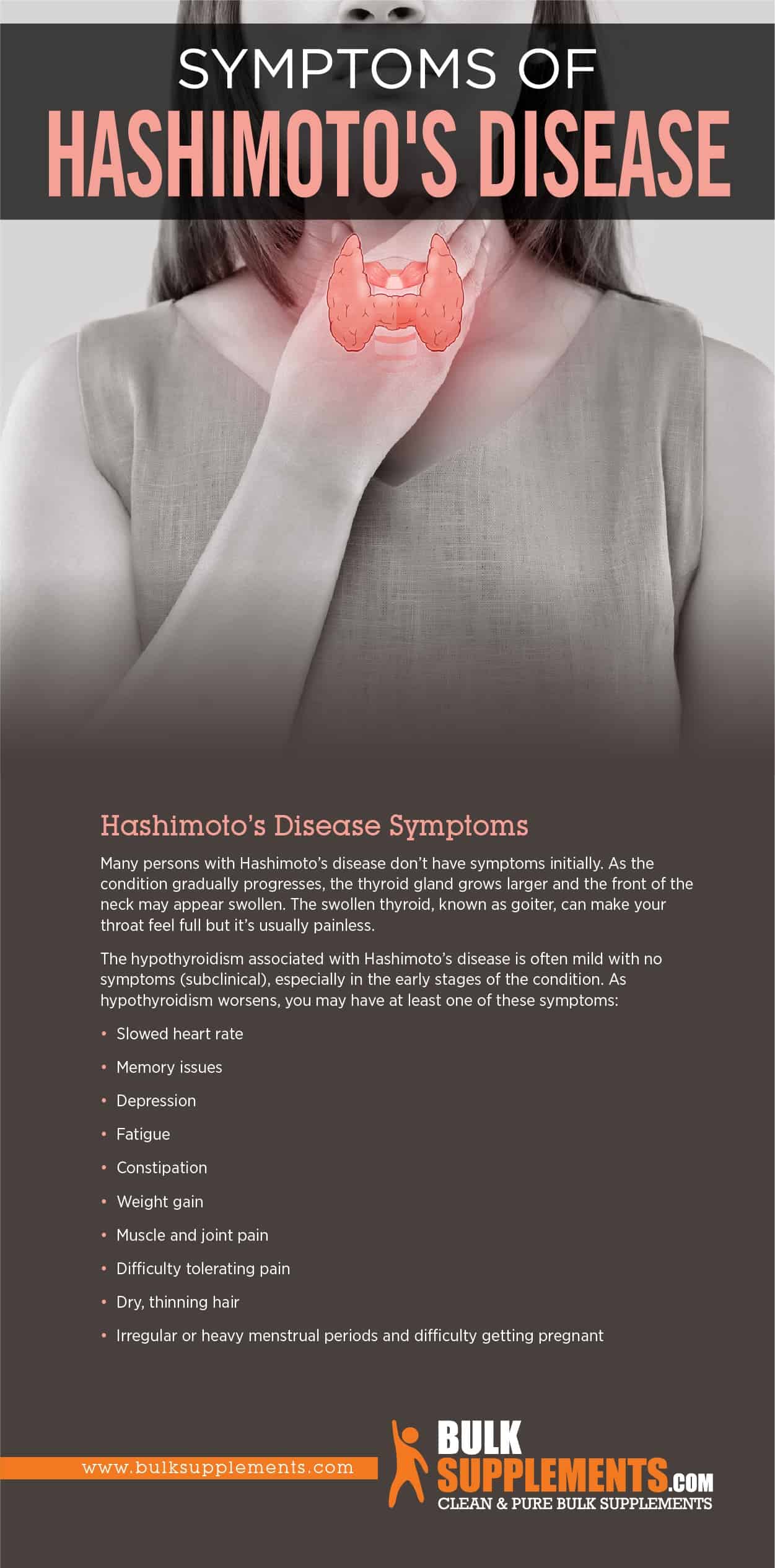

Hashimoto’s Disease Symptoms

Many people with Hashimoto’s disease don’t have symptoms initially. As the condition gradually progresses, the thyroid gland grows larger and the front of the neck may appear swollen. The swollen thyroid, known as goiter, can make your throat feel full but it’s usually painless.

The hypothyroidism associated with Hashimoto’s disease is often mild with no symptoms (subclinical), especially in the early stages of the condition. As hypothyroidism worsens, you may have at least one of these symptoms:

- Slowed heart rate

- Memory issues

- Depression

- Fatigue

- Constipation

- Weight gain

- Muscle and joint pain

- Difficulty tolerating pain

- Dry, thinning hair

- Irregular or heavy menstrual periods and difficulty getting pregnant

Hashimoto’s Disease Causes

Doctors are unsure why Hashimoto’s disease occurs. Some researchers believe it could be due to exposure to a virus or bacteria, while others think that genetics could be the culprit. No matter the cause, here are some possible causes of Hashimoto’s disease.

Autoimmune Disorders

Having another autoimmune disorder increases your risk for getting Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. The reverse is true, too, and some autoimmune disorders are linked to Hashimoto’s disease, including alopecia, celiac disease and type 1 diabetes.

Genetics

There are a number of hereditary genes linked to Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, but the most common include HLA-DR3 and HLA-DR5. These genes are more prevalent in Caucasians. But having either of these genes is no guarantee that you’ll definitely get Hashimoto’s disease. It simply means you have a higher risk.

In addition, family members of individuals with Hashimoto’s disease have a greater risk of developing the condition. And since it’s more common among women, female family members carry the highest risk. In particular, children of people with Hashimoto’s disease are up to nine times more likely to develop the disease. Twins are also more likely to exhibit Hashimoto’s thyroiditis than everyone else.

Thyroid Antibodies

People with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis are more likely to have thyroid antibodies. Often, antibodies associated with Hashimoto’s disease can be in high amounts for many years before a Hashimoto’s disease diagnosis is made. High levels can seem normal during testing, but the thyroid can’t produce enough hormones anymore.

While most individuals with Hashimoto’s disease carry specific antibodies, around 5 percent don’t have measurable thyroid antibodies. Those without antibodies often have a milder version of the disease.

Age

The risk of developing Hashimoto’s thyroiditis increases with age. For women, people with autoimmune conditions or people with a history of the disease in their family, the risk is even higher.

Gender

Hashimoto’s disease mostly affects women. Researchers believe that sex hormones have something to do with it. Some mothers also have thyroid issues within the first year of giving birth. Those thyroid problems tend to go away, but it’s possible that some women may develop Hashimoto’s disease later.

Menopause

Reduced estrogen amounts during menopause can affect thyroid function. In a certain peer review study, researchers were able to suggest a link between thyroid function, estrogen levels and the occurrence of thyroid conditions. But they weren’t exactly sure what the link was and cited how further studies were needed.

Too Much Iodine

Too much iodine has been thought to cause Hashimoto’s disease as well as other forms of thyroid issues. In one study, researchers from China studied the effects of iodine supplements on the thyroid gland. The researchers found that giving iodine to subjects who had excessive or adequate iodine levels upped the risk for Hashimoto’s disease.

Bacterial Infections

Like other autoimmune conditions, Hashimoto’s disease can be caused by various parasitic, fungal, bacterial and yeast infections that originate in the digestive tract. You don’t necessarily have to have symptoms to be attacked by these kinds of stomach bacteria.

Sadly, most of the research isn’t that specific to determine exactly how bacterial infections can cause autoimmune thyroid disorders or how to lower risk factors.

Radiation Exposure

Research has shown a connection between radiation exposure and Hashimoto’s disease. The condition is common in people who’ve had exposure to radiation during cancer treatments. Also, it’s more pervasive in people exposed to radiation due to nuclear events.

Complications

Studies show that individuals who have autoimmune and thyroid disorders that are untreated may later suffer from the following health problems:

- Serious infections

- Neurological damage

- Kidney and brain problems

- Mental disorders like depression

- Increased risk of heart disease and high cholesterol levels

- Graves’ disease or Addison’s disease (other thyroid conditions)

- Thyroid goiter, resulting from an enlarged thyroid gland, which can then disrupt normal swallowing and breathing

- Type 2 diabetes

- Ovarian failure, infertility, pregnancy or birth complications or birth defects

Living with Hashimoto’s Disease

Hashimoto’s disease remains stable for years. If it progresses to become hypothyroidism, it’s easily treated.

As Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is an autoimmune and inflammation disease, lifestyle changes can be a beneficial addition to medical treatment.

Adopting a plant-based diet rich in fresh vegetables, fruits, healthy proteins, whole grains and healthy fats (nuts, seeds, eggs, fish, avocado) and cutting out processed foods is a good place to start.

An integrative nutritionist, medical doctor or naturopath may help you find out which foods might be causing the inflammation. Other lifestyle changes shown to lower inflammation include restful sleep, regular exercise and stress management methods (like meditation).

If you plan to get pregnant and you have Hashimoto’s disease, you should consult your doctor. If left untreated, hypothyroidism may affect you and your unborn child. You have to be careful and monitor hypothyroidism symptoms throughout your pregnancy.

Treatment for Hashimoto’s Disease

If your condition is serious enough to lead to hypothyroidism, you may need treatment for Hashimoto’s disease. If you have no hypothyroidism, your doctor can simply choose to monitor you to check if the condition gets worse.

Medical Treatment

Hashimoto’s disease normally responds well to thyroid replacement therapy. The patient is treated with levothyroxine, an artificial type of T4. Most individuals need regular monitoring of TSH and T4 levels, as well as lifelong treatment.

Dosage adjustment is required to keep T4 and TSH levels in the normal range. One can easily slide into hypothyroidism, a condition that’s especially harmful to bone and heart health.

Symptoms of hyperthyroidism can include an irregular or fast heart rate, fatigue, nervousness/excitability, sleep disruption, headache, chest pain and shaky hands.

Surgical Treatment

There’s rarely a need for surgery, but if it’s necessary, it may be a sign that the goiter is large and causes cancer or obstruction. Surgery can also address cosmetic issues if the goiter looks unsightly.

Best Supplements for Hashimoto’s Disease

Certain supplements lower immune reactions and help your body cope with stress better; they also assist with controlling immune system activities. They include:

Ashwagandha

Ashwagandha helps relieve adrenal and thyroid problems by making you cope better with balance and stress hormones. Research proves that it also balances the T4 thyroid hormone, which is critical for overcoming Hashimoto’s disease or hypothyroidism.

Take 450 mg of this supplement once to thrice daily, or as instructed by your physician.

SEE ALSO

Lupus: Causes, Symptoms & Treatment

B Vitamins

B vitamins, especially vitamin B12, are essential for maintenance of energy and many metabolic and cellular functions. Dubbed the “energy vitamin”, vitamin B12 supports regular cellular functions that combat fatigue.

In one study, patients with Hashimoto’s disease were given 600 milligrams of thiamine daily. Most of them experienced full regression of tiredness within hours to days.

Consult your doctor about the right vitamin B12 dosage for you.

Magnesium

The magnesium oxide supplement benefits digestive and heart health. It’s also an antacid that can relieve indigestion.

Take 700 mg of magnesium oxide once daily with water. If you suffer any stomach discomfort, take this supplement with a meal.

Thiamine

Also called vitamin B1, thiamine may boost energy, support weight management and promote immune and heart health. It may also improve memory, focus and mood.

It’s recommended that you take thiamine in dosages of up to 100 mg daily, depending on your doctor’s recommendation and your intended effect.

Selenium

Selenium is beneficial for the thyroid as it’s been proven to regulate the T3 and T4 hormones in the body. It may also decrease the chances of thyroiditis during pregnancy and afterwards.

A diet without enough selenium and iodine ups the risk for Hashimoto’s disease as the thyroid gland requires both iodine and selenium to produce sufficient amounts of thyroid hormones.

One study found that people with took selenium supplements experienced a 40 percent decrease in thyroid antibodies in general compared to a 10 percent increase in those who didn’t take selenium.

Talk to your doctor about the right dosage of selenium for you.

The Bottom Line

Hashimoto’s disease, also called Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, autoimmune thyroiditis or chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis, is an autoimmune condition which occurs when immune cells wrongly turn against healthy thyroid tissue, resulting in an underactive thyroid (hypothyroidism).

Hypothyroidism is the disorder in which your thyroid doesn’t make adequate hormones for your body’s needs. Symptoms of hypothyroidism (underactive thyroid) include weight gain, feeling cold when other people don’t, fatigue and heavier-than-usual menstrual periods.

You may not have any Hashimoto’s disease symptoms for many years. The most common sign is often goiter — an enlarged thyroid. The goiter can make the front part of your neck appear swollen. You can feel it in the throat, or it can be difficult to swallow. However, most people have no symptoms at all and goiter rarely causes pain.

A variety of risk factors can contribute to the occurrence of Hashimoto’s disease. Genetics, gender, age, menopause, autoimmune conditions, excessive iodine and bacterial infections are some of the possible causes.

Not all people with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis have hypothyroidism. If you don’t lack thyroid hormones, your doctor can recommend regular monitoring instead of treatment with medication. But if you’re short of thyroid hormones, treatment includes hormone replacement therapy. Levothyroxine is the most common treatment for Hashimoto’s disease