The PhotoGuides Guide to Photography

How Cameras Work

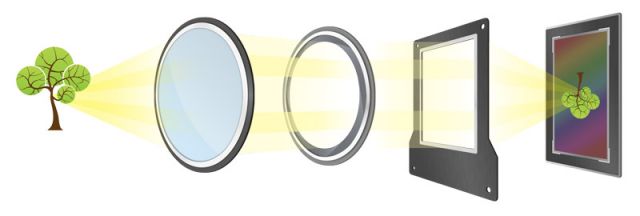

The digital camera is a beautifully simple piece of technology. Every camera, be it film or digital, works in the same basic way. Light from the scene beams through your camera’s lens, through the aperture, through the shutter and onto your camera’s film or sensor. This light paints our photograph.

Point and Shoot cameras are cameras with fixed, non interchangeable lenses. Point and Shoot cameras are generally compact and automated. The camera manages everything for you automatically, leaving you to just point the camera at the scene and shoot the photo. Point and Shoot cameras are becoming more capable, but they will never match the overall image quality of an SLR.

SLR CaMERAS

SLR stands for Single-Lens Reflex. SLRs are the larger, more ‘professional’ looking cameras that allow you to change lenses and delve deep into the settings. The name SLR explains the mirror and viewfinder system within the camera. Light comes through the lens, bounces off a series of mirrors and can then be seen through the viewfinder. By changing lenses you can explore new realms of photography, from macro to zoom, from wide angle to tilt shift. SLRs are wonderfully expandable, incredibly capable cameras.

Megapixels

Every digital camera contains a digital sensor that captures light and creates your photograph. Your photograph is made up of millions of dots of light. Each tiny dot of light is called a pixel, so your camera’s Megapixel specification denotes the size and resolution of your photos. More megapixels will allow you to print your photographs in a larger size or zoom in further on a computer. Be careful though when looking at cameras. More megapixels don't always mean a better quality photo. Some cheap, high megapixel cameras can produce noisy, low quality images. Megapixels are an important characteristic of a camera, but they don't mean everything.

Aperture

When you’re in a dark room, the pupils in your eyes will dilate to let as much light in as possible. Switch the light on and you’ll find that your eyes instantly contract so that you’re not blinded. On a camera, the aperture works in a very similar way. It expands to let in more light when it’s needed, and in brighter situations it shrinks to ensure your photo isn’t over exposed.

By controlling your camera’s aperture you are controlling the amount of light that enters the lens. Aperture is controllable by a measure known as F-Stops. Each F-stop represents a different level of expansion or contraction. A smaller F-Stop, such as F2.8 represents a larger aperture and a wider opening. A larger F-Stop however, such as F22 denotes a smaller aperture and smaller opening.

Aperture can be controlled by switching your camera to Aperture Priority mode (A) or to Manual mode (M). There you’ll have the ability to adjust the Aperture in set increments. Cameras generally have around 10 aperture increments to choose from.

By changing your aperture you have the ability to manipulate the exposure of your photo, as well as your photo’s Depth of Field. This is something we will discuss in the next section.

The best way to learn about aperture is to play around with it. Switch your camera into Aperture Priority or Manual mode and look at the effect changing your aperture has on your photo, as well as on your other settings.

Depth of Field

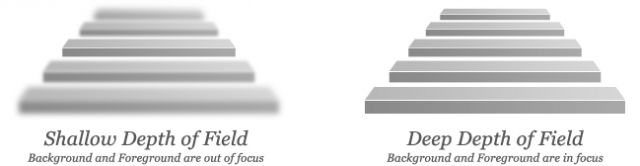

The Depth of Field (DOF) refers to the range of in-focus visibility of the shot, or, in other words, how far you can clearly see.

In photos where the subject is in focus and the background and foreground are blurred out, just like in the image on the right, this effect is a result of Depth of Field. In this case we say the photograph has a shallow depth of field. Alternatively, we can clearly see a significant distance, we say it has a deep depth of field.

Manipulating the Depth of Field is very straight forward. A wider or larger aperture (such as F2.8) will give you a shallower depth of field, and a smaller aperture (such as F22) will result in a deeper DOF and give you a greater viewing distance. The smaller the aperture, the greater the range of visibility in your shot will be.

A shallow depth of field works well when you’re photographing people. A nicely blurred background will help to separate the person from their surroundings. If your camera has a ‘Portrait’ mode, then this automatically uses wider apertures to create the shallowest depth of field possible.

A deeper depth of field is more effective in landscape photography. A higher range of focus is perfect for capturing those finer details. The ‘Landscape’ mode on your camera will choose smaller apertures to automatically create a deep depth of field.

The best way to learn about Depth of Field is to play around with it. Pick an object to focus on and see how your DOF changes when you manipulate your aperture.